Abstract

Background Hematology-related and other cancer clinical trials provide the treatment standards necessary to direct care and, in many cases, provide access to life-saving therapies for patients. However, Black persons remain underrepresented in US clinical trials. This lack of diversity contrasts with the disproportionate burden of incident cancer cases and deaths among Black persons. Multiple factors (e.g., individual, interpersonal, and health care system) contribute to the disparate burden. Among them is the patient-physician relationship. Underlying this relationship is the complex hierarchal structure that creates additional challenges when enrolling Black participants in clinical trials.

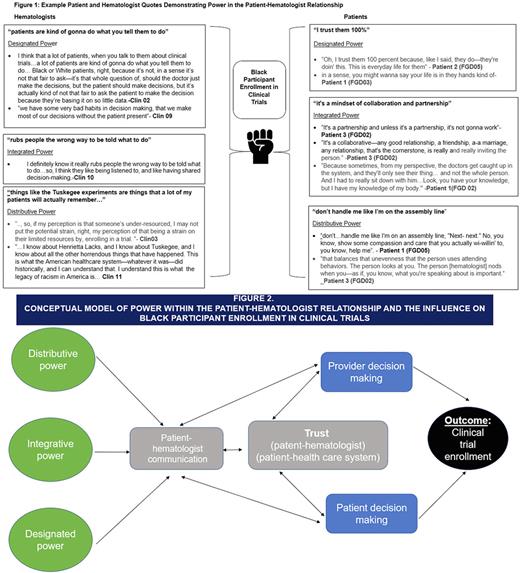

This study aimed to understand how power, defined as the degree of control over material, human, and intellectual resources (Miller et al., 2006), is exercised within the patient-physician (hematologist) relationship and how the hierarchical power structure influences Black participant enrollment in hematology clinical trials.

Methods Between August 2021-January 2022, we recruited hematologists to participate in a 1:1 interview and recruited Black patients with multiple myeloma to participate in focus group discussions (FGDs). We used the Sort and Sift, Think, and Shift qualitative data analysis approach (Maietta et al., 2021), which included memoing and diagramming to assess topics and identify themes. We applied the Relational Theory of Power (Hocker and Wilmot, 1995) which explores power as a characteristic of social relationships that influences communication. Based on this theory, power can be: 1) designated (power based on one's position), 2) distributive (power over or against someone else), and 3) integrative (shared power). We examined these 3 types of power within the hematologist-patient relationship to understand the impact on Black participant clinical trial enrollment.

Results We interviewed 13 hematologists and conducted 6 FGDs with 23 patients. Both patients and hematologists expressed awareness of existing power differentials within the hierarchal structure of their relationship and the influence on communication about clinical trials. The relationship structure created patient discomfort about raising the possibility of clinical trial participation or asking clarifying questions from their hematologist about clinical trial processes. Furthermore, some patients ultimately deferred the decision to participate in a clinical trial to their hematologist. Patients grounded this preference in the physician's knowledge, role, and expertise (designated power) (Fig 1). When discussing clinical trials, hematologists emphasized the need for transparent and empathic communication and understanding patient preferences and goals. Some patients viewed their enrollment in a clinical trial as a partnership between themselves and their hematologist (integrative power). Both patients and hematologists acknowledged the legacy of medical mistrust induced by past research where Black persons were intentionally harmed (e.g., Tuskegee experiments). This and other historical events (e.g., the story of Henrietta Lacks) were viewed as examples of distributive power where researchers and clinicians used their power to dominate and potentially manipulate their research participants. Patients and hematologists acknowledged that these events were a persistent barrier to Black participant clinical trial enrollment. Within the structure of the patient-hematologist relationship, these three types of power influenced the communication between Black patients and their hematologists about clinical trials. This communication also influenced whether a patient trusted the clinical trial process and ultimately influenced clinical trial enrollment (Fig 2).

Conclusions This research reflects the power structure within the patient-hematologist relationship and how these three types of power could influence a Black patient's decision to enroll in a clinical trial. While the patient-provider relationship represents only one of several determinants of trial participation, it is likely one of the most influential factors. Therefore, interventions are needed to improve communication, build rapport, and address power differentials between hematologists and their patients to enhance the recruitment of Black participants in clinical trials.

Disclosures

Tuchman:Prothena: Honoraria; Shattuck Labs: Honoraria; Janssen: Honoraria.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.